What a year we have had in 2022 – challenging all scanning models, scenario gaming and risk assessment. The perception of ‘fragile peace’ was broken with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Along with COVID, it also revealed the fragility of Globalisation 2.0, the vulnerability of the global supply chain, questioning the Chinese growth model and the chinks in the unipolar world order led by the United States and its Western allies, a so-called West vs. the Rest. From semiconductors to energy to international trade and payments systems – there were attempts to weaponize and nationalize crucial business segments. Businesses realized that geopolitical threats were imminent – essential resources could be taken off the table suddenly (e.g., Russian energy), geographies of operations could become hostile, and sanctions, lawfare and political backlash were a clear and present danger.

Yet it was also the year of mid-powers who have traditionally punched below their political-economic weight to take centre stage and forge self-interested alliances to reshape the global trade, finance, and power systems. It was a year when localized countries and geographies emerged as ‘islands of opportunities’ amidst a larger bleak environment. There were strides in some key sectors – digitization and technologies of the future, an accelerated shift to clean energy and attempts to re-shore critical assets. These trends opened up new venues and opportunities for companies and businesses.

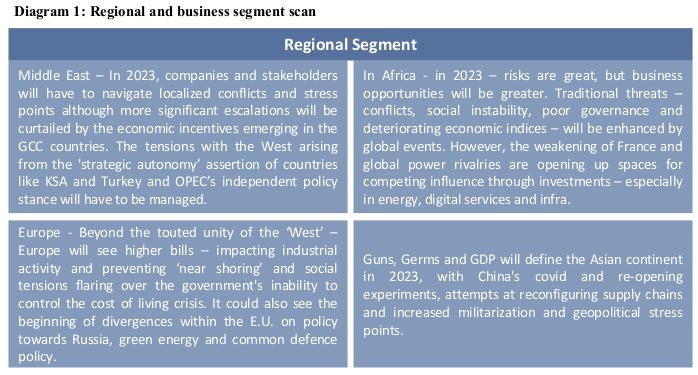

These trends will likely continue in 2023, governed by the 3C’s– Covid, Conflict and Climate Change. Covid signifies the black swan events – sudden, unexpected occurrences with far-reaching impact.

Conflict denotes a breakdown in the consensus and certainty of the global political and economic order.

Climate change represents the long-term structural changes in the world economy, polity, and demographics. Together they will create themes and risks that are enumerated below:

- Heightened Conflicts/Global Stress Points

The Ukraine conflict will continue to be central in world affairs, but in 2023, the world will learn to live with the stalemate in the war. Escalation without provoking a broader contagion is hard despite alarmist reports. Peace negotiations seem equally difficult given that demands on both sides are ‘red lines’ for the other. But the odds are that as the EU faces another winter without Russian energy, West vs. the rest on the issues grows stronger, and U.S. strategic goals are fulfilled – fragile peace proposals will begin to do rounds in 2023. Fruition might be delayed until 2024, but the ‘Ukrainian saga’ is far from over.

Beyond Ukraine – geopolitical eyes will turn to the Indo-Pacific, where unprecedented military build-up is taking place. North Korea is the most public, but China is on a militarizing spree, and Japan is now out of Self Defence mode. India is building up its border defenses, Taiwan is trying to draw lessons from Ukraine, and the U.S. is encouraging all of this. The U.S. is also trying to bind countries like India, Australia and Japan through alliances – the AUKUS (Australia-UK-US) and the Quad intended to deal with China’s geopolitical and military rise.

I would also watch the conflicts frozen/kept low-key due to the force field between superpowers. Ironically Russia maintained a status quo in its sphere of influence & with its diversion in Ukraine, its immediate neighborhood is becoming a contested zone of superpower rivalries. Armenia-Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Mongolia – could be harbingers of a broader conflict in an unstable area. In areas where Russia is the security partner, and China the leading economic/infrastructure partner – risks will be heightened.

2. Alliance Systems Will Shift and Disrupt

Enough has been said about the recent challenges to the U.S.-led unipolar world order that has been in effect since the late 1970s. What is emerging now is an ‘untethered political system’ where unipolarity is waning, but no clear bipolarity exists. Instead, there are two sides – the U.S. and its allies and China/Russia and their partners. In the vaccum, several mid-powers are ‘de-aligning’ and exercising their national and opportunistic interests, often playing the superpowers off each other. The result is going to be uncertainty.

Some trends stand out in this regard.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, many commentators have touted the unexpected unity between the U.S., the U.K. and the European Union in responding to the military, economic and energy-related crisis. From unified sanctions, to supply of aid, weapons and training to Ukraine to rallying global nations against Russia and finding solutions to the energy crisis – there has been a swift, unified movement not typically seen in a big bureaucracy like the E.U. However schisms are emerging within the E.U.:

Divergences between France and Germany on issues ranging from energy security (nuclear vs. other sources) and common electricity market to the EU’s common defense policy and long-term response to the Ukrainian crisis.

Eastern vs. western Europe/periphery vs. core E.U. as countries like Poland and the three Baltic states are trying to increase influence within the E.U. using the framing of security policy against Russia as a conduit.

Uneven economic impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war could start weakening the united front in 2023 – especially if the predicted recession sets in and subsidies get costlier.

Emerging ‘Global south’ alliances can begin to cause disruptions to the existing world order. Of particular interest is the emerging bonhomie between China and the energy and cash-rich Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – especially Saudi Arabia. Only tortoise steps of Globalization 2.0. will emerge in 2023. But with increasing trade between emerging economies, talks about dealing in local currencies, oil for gold and Central Bank digital currencies, the impact could be far-reaching. The dollar dominance may not be going anywhere soon. Still, challengers in the form of the petro-yuan framework, countries like Saudi Arabia in BRICS, and events such as Russia-Iran bank linkages are emerging as challengers.

3. Economic Doom and Gloom?

Recession, hard or soft landing, China’s chaotic or orderly re-opening, prospects for U.S. slowdown, Europe’s energy inflation – economists and market pundits will continue grappling with these concerns in 2023. Economic statistics have steadily improved in the fourth quarter of 2022, with inflation rates coming down, surprise growth in the Eurozone and better-than-expected Covid management in China –creating a false sense of complacency. As of now, the recession/economic slowdown might seem milder than anticipated. However, inflation caused by structural supply-side constraints, uncertainty driven by geopolitical events (most notably, the Russia-Ukraine conflict) and a painful transition in the energy markets will ensure that the sword of economic volatility becomes part of business decision cycles.

Beyond markets and short-term projections, businesses will have to develop robust mechanisms to monitor and respond (through risk assessments, diversification and non-financial risk matrices) to four key factors impacting macro-economics:

The uncertain trajectory of the Russia-Ukraine war/’perma crisis’ events

Superpower rivalries and how trends of sanctions and supply chain controls work out

Uncertain energy transition

Structural events such as climate impact and an aging workforce, especially in China.

4. Nationalization and Weaponization

Businesses will have to prepare for a Thucydides Trap – where an emerging/resurgent power threatens to displace an existing dominant force and how the dominant force will preserve its hegemony. Several countries and neutral stakeholders will be caught in the middle and forced to take sides.

There will be attempts to WEAPONIZE everything – trade, finance, technology, rare earth minerals, and energy.

Policy decisions to reduce the impact of weaponization and attain self-sufficiency can lead to NATIONALIZATION in critical sectors. The Inflation Reduction Act and the Semiconductors and CHIPS Act in the U.S., the European attempts to prevent the flight of companies from the E.U. (due to high costs) and the Chinese re-assertion of state control – have compromised the collaboration on energy, supply chains and technologies of the future. In 2023, this trend will also create opportunities in new markets as companies attempt to reconfigure/diversify supply chains. Businesses will also try to circumvent tit-for-tat sanctions and export restrictions in key sectors.

A major impact of nationalization and weaponization and changing geopolitical realities will be on the transition from high-carbon production to low-carbon alternatives. In 2023 – the disruptions will be most prevalent with a mad scramble for fossil fuels – oil, gas, and coal, especially as the market for the former has been fragmented due to sanctions on Russia. Attempts at transforming to ‘cleaner’ sources will be met with political challenges, supply chain anomalies, climate events and future storage technologies. A transition to clean energy is the writing on the wall – but in 2023, it will be a painful shift, creating new winners and losers.

5. Clash of the Civilizations?

There has been enough limelight on a resurgent Russia and an internally weakened but outwardly aggressive China. However – I would most closely look at a polarized United States whose dominance is being challenged on all fronts as creating the maximum risks in 2023 and beyond.