By Basant Raj Bhandari

The international trading system and supply chains in 2023 will see two contradictory and destabilising trends. First will be the increasing distance between the economies of the two superpowers –the U.S. and China and their partners. This trend has already manifested in Russia. For China, it can take the following forms:

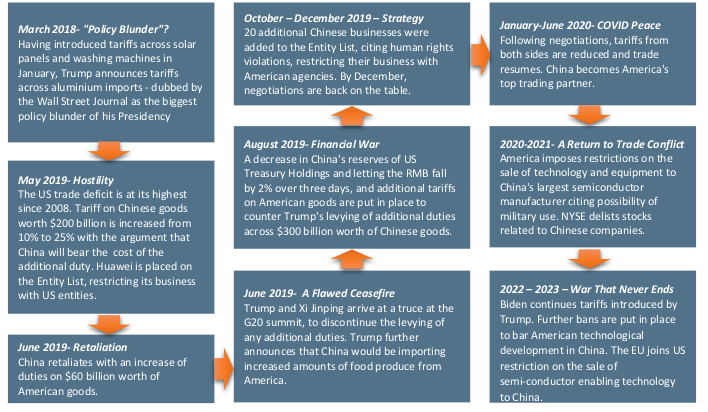

- Trade wars

- Sanctions, Export restrictions and Lawfare

- Re-shoring, near-shoring and friend-shoring of critical supply chains will involve massive government subsidies distorting the WTO-led rules-based global trading system

- Weaponisation of finance, trade, energy, rare earth minerals, and high tech components

- Economic alliances for geopolitical containment, such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework

However, in 2023 – this distance and the pressure on the others to fall in line will be challenged by self-interested ‘minilateralism’ by the newly assertive middle powers who seek to reshape the western dominance of the trading, currency and financial system. The characteristics will include the following:

More trade between Emerging economies (E.M.s) through bilateral and mini-lateral agreements.

Mid-powers forming alliances on specific issues while maintaining their strategic autonomy – I2U2 (India, Israel, UAE and U.S.) alliance is a good example.

Third, the attempts to bypass the dollar-led financial payment system. Because of its excessive weaponization, and strength in the face of volatility and inflation, many countries will try alternative arrangements. These can include proposals for petro-yuan, trading for oil in local currencies, gold for oil, and the proposed BRICS payment system. These attempts are far from fruition, and it is a long way to see if they can challenge the dollar dominance, but in 2023 such narratives and efforts will abound.

Many experts have cited the increasing trade between E.M.’s, alliances between mid-powers and new growth areas in the ‘Global south’ – as an example that globalization is far from over, just being re-directed. There are some overpowering statistics to support this assertion. Consider these:

Global trade is estimated to grow at 12% and cross the US$31 Trillion mark in 2022; services are about a fifth of Goods turnover. There have been High trade growth despite the pandemic, the Ukraine war and US-China tensions. In 2023 – economists expect that despite a slowdown in growth due to energy prices, inflation in the U.S. and Europe, and disruptions in high-tech supply chains – global trade can grow by 5%, led by new hotspots – India, GCC, SE Asia and Mexico.

But you go beyond the numbers, and the truth is that the era of globalization that began post the Second world war and strengthened with the Chinese opening up & collapse of the USSR – was underpinned by the economic priorities and the might of the U.S. Global supply chains were based on the certainty of the dollar and western financial models & backed by U.S. military control over high seas. Many of these parameters are now changing.

Viewed in this light, ‘Globalization 2.0’ or E.M. globalization will be inherently unstable, prone to protectionist impulses and increased global stress points. In 2023 this will erode the confidence companies have enjoyed over the years to operate internationally, making it harder to plan operations, supply chains and business models.

In the mid-2000s, the German saying ‘Wandel durch Handel,’ meaning trade will trump conflicts, described the West’s relationship with China and Russia. There was often an emphasis that the Apple supply chains kept the peace in the Indo-Pacific with their vast expanse in the U.S., China, Taiwan and Vietnam, creating incentives for keeping tensions in check. However, with the switch to efforts for China’s strategic containment through U.S. policy, reshoring of supply chains (no matter how much time they take or back and forth) and E.U.’s national security debates – the adversarial economic relation has been well-defined. In 2023, the U.S. will continue with restrictions and controls, and the Chinese are likely to respond with their measures – economic and geopolitical, such as the anti-foreign Sanctions Act. Europe will vacillate between appeasing China for a continuation of supply chains as its Russia-related problems explode and trying to protect its key sectors from being ‘gobbled’ up by Chinese investments.

Some countries, like India and South East Asia, could benefit from the re-orientation of the supply chains. The mid powers will try and offset the impact of superpower rivalries by a) forming bilateral/regional agreements or b) maximizing their self-interest or playing big powers’ against each other, e.g., Saudi Arabia’s vacillation towards China. The result will be an opportunistic world where the rules of trade, international payments, resource availability and supplies are fast changing. As the world divides itself into economic-political power blocks, companies will have to de-risk supply chains, handle the sudden loss of legitimacy in specific geographies and the impacts of crucial resources being taken off the table by geopolitical events.

2023 might be the year where the extreme impact of trends seen since 2020 – covid, conflict, inflation, supply chain disruption can plateau–giving the world a breather. However, nationalization and weaponization will continue to create uncertainties for trade and economic cooperation. The repercussions will be felt far beyond the economic realm – with increasing militarization in the Indo-Pacific, the threat of accidental escalations, cyber warfare and forming of ‘unholy’ geopolitical alliances.

Leave a Reply